“…more than is possible in theatre or film”

An interview with Ralph Trommer about graphic adaptations of literary works

More and more literary classics are being adapted into elaborate comic books and graphic novels. Under the heading “The second look: 32 comic adaptions from Babylon Berlin to Marcel Proust” , the Frankfurter Buchmesse is presenting a collection of this type of comic book, with a focus on Berlin, at its collective stands at book fairs abroad. Time for an interview with the curator of the “Babylon Berlin” collection: Ralph Trommer, comic-book expert and culture journalist for taz, Der Tagesspiegel and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, amongst others.

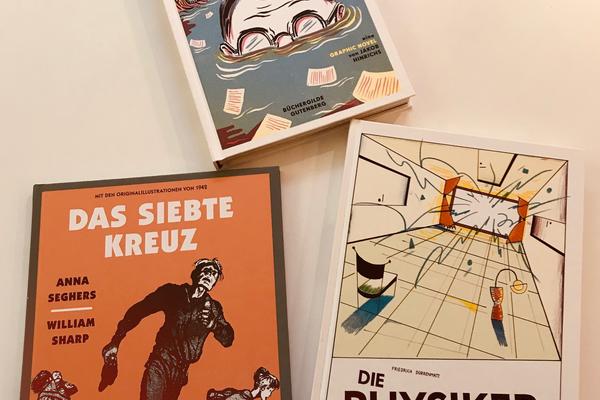

Fallada’s “Der Trinker” (“The Drinker”), Dürrenmatt’s “Die Physiker” (“The Physicists”) – the collection “The second look: 32 comic adaptions from Babylon Berlin to Marcel Proust” offers many adaptations of literary classics. Is this sort of content a new trend in the comics scene?

In the early days of comic strips, there were already numerous adaptations of classics, such as the first “Tarzan” comics by Hal Foster around 1930. Later, there were also series like “Illustrierte Klassiker” (“Illustrated Classics”) in Germany. “The Seventh Cross“ is an example of a very early adaption of an extremely topical work by Anna Seghers during the Second World War that quickly became a classic. However, the majority of comic books are based on original ideas. With the graphic-novel boom of the last two decades, the number of adaptations has also increased. This has to do with the improved image graphic novels enjoy within the literary scene. Ever since, it has been possible to tell ambitious stories in this sector, including based on already famous literary originals. Which classics are chosen depends on a given artist. Or there is a commission – for example, from a publisher who wants to call renewed attention to a certain classic through a graphic-novel interpretation. Today, the artists themselves decide based on individual criteria: they can choose whether to tell their own stories or to put their style to the test in interpreting a classic.

What qualities should a novel have to be adapted successfully into comic-book form? Are there any exclusion criteria?

Generally speaking, there are no exclusion criteria for the art, but there also aren’t any watertight criteria for success. In my opinion, it depends entirely on the inspiration that a work, a novel, sparks in a given illustrator or scriptwriter, who, after all, initially is just a “reader” and only subsequently has to develop his or her own vision. You can sense when a graphic novel isn’t just a routine adaptation of an original, but has inspired the artist’s imagination to produce his or her own “recreation” of the work. Both trivial material (e.g. “Malcolm Max”, “Three Investigators”, “Mark Brandis”) as well as world literature (by Anna Seghers, Edgar Allan Poe, Marcel Proust) is suitable source material. Today, even diaries can be transposed effectively into comic-book form (“Mühsam”). However, there is also a series of less successful adaptions that transpose works into images 1:1, without creating artistic value-added. For example, to date there are hardly any good adaptations of Kafka, even though there have been many attempts. A good adaptation succeeds in offering an independent look at the work; it can be very free – one example is Lukas Jüliger’s adaptation of “Berenice”, which transforms Poe’s text into something very contemporary. Or Lorenzo Mattotti’s interpretation of “Hansel and Gretel”, which is also a stand-alone artwork that captures the spirit of the original.

What is successful ultimately also depends on the zeitgeist, which is probably somewhat coincidental. Reinhard Kleist’s “Nick Cave” comic seems to me to be a good example of an artist immersing him or herself in a topic so obsessively that you can feel it as a reader.

Biography, fiction, diary, play – can all literary genres be turned into good comic books thanks to cross media publishing?

Yes. Just as today’s theatre scene often uses novels and films as the basis for stage plays, comic books can also transpose a given topic from another medium into their own. In fact, they can probably do even more than is possible in theatre or film since comic-book illustrators create their own worlds with the help of their pencils, the selection of colours or with the aid of a computer. These can be elaborate fantasy or science fiction worlds, but Nicolas Mahler’s minimalistically illustrated comics also evoke their own convincing reality that lasts for the duration of the reading experience. The already popular crime fiction genre has also proven itself in comics. There are many examples of successful series that transpose originals into atmospheric visual narratives, from Dashiell Hammett’s “Fly Paper” to “Wilsberg” to Volker Kutscher’s novels. Perhaps the most extreme example is Jens Harder’s transformation of the millennia-old epic of Gilgamesh from stone tablets into an “antique” comic.

Digitalisation keeps bringing us new storytelling formats: e-books, apps, games, GIFs, emojis and many others. What does digital development mean for the comics scene?

Perhaps it leads to new possibilities for presenting and distributing comics, which can now be read everywhere in completely different contexts. However, these possibilities are still at an early stage of development. To date, the classic form on printed paper is still the most successful; yet many titles are also already available as e-books. While technically, formally, there are innovations like Daniel Lieske’s “infinite screen” (“Wormworld Saga”), they rarely catch on across the board. Animated comics, for example, result in animated movies. Comics themselves have other means of expression. Ultimately, for all avid comic-book readers, the haptic experience of reading on paper is simply more sensory than reading comics on a screen.

To wrap up, let’s return to the collection again: What’s special about Berlin as a setting – even for international audiences?

Berlin is en vogue at the moment – and may continue to be so for many years to come. That’s because the city reflects the extremely historically dense 20th century. Stories can be told about the exciting interwar years, which encompassed a fresh start for society and ended in a historical downward spiral. The Nazi period is another Berlin era that is full of upheavals that can be transposed vividly into images. Finally, the Cold War and German reunification are also important periods that continue to influence people now. Maybe Berlin is so “hip” today because, like in the 20 years after the fall of the wall, it is once again in the midst of a period of transformation. Visualising the past is usually more interesting than representing the immediate present right outside our doorstep. Great illustrators who make a point of properly researching backgrounds and costumes can create particularly striking reconstructions of an era in comic books. “Der kalte Fisch” (“The Wet Fish”), illustrated by Arne Jysch, is something like the Berlin answer to Léo Malet’s Paris-based thrillers featuring Nestor Burma from the pen of Jacques Tardi. However, all graphic virtuosity notwithstanding, it’s important to remember to meet the many open questions of the last century not only with elaborate illustrations, but also through intelligently told stories.

Thank you very much for this interview, Mr Trommer!

(This interview was conducted by Frank Krings, PR Manager of the Frankfurter Buchmesse.)

All information about the book collections of the Frankfurter Buchmesse is available here(Öffnet neues Fenster).