"Because it’s not enough for us to have one or two books about deaf people and tick that box; we need a whole bookshelf."

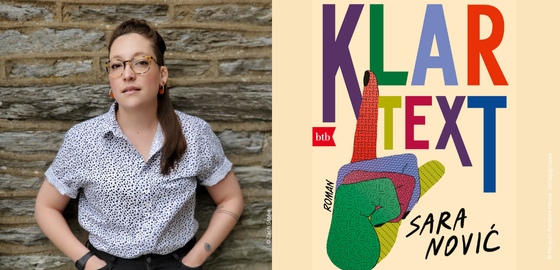

© Zach Stone, Penguin Random House Verlagsgruppe

Sara Nović is the author of the New York Times-Bestseller novel "True Biz" (2022, Random House, German Translation from Judith Schwaab, "Klartext", 2025, btb) and "Girl at War" (2015, Penguin Random House Pocket), which won the American Library Association’s Alex Award. Sara teaches Deaf studies and creative writing and lives in Philadelphia with her family.

In our interview, Sara shares her experience of becoming an author and writing "True Biz", she talks about the power and humour of American Sign Language (ASL) and her hopes for the representation of marginalized voices like people with disabilities and the LGTBQ+ scene in literature.

Sara, thank you for doing this interview with us. We are very thrilled. First of all, do you have books that resonated with you while growing up?

Thanks for including me! I was an avid reader growing up. Books were one of my favorite ways of learning and also an escape hatch for me, especially when I started losing my hearing. As a kid, I really loved choose-your-own-adventure novels and mysteries; I read all the Nancy Drew books in my school’s library, and a lot of Agatha Christie. These days I read much more broadly, but I still have a soft spot for a good thriller when I don’t guess the twist.

I remember getting into Vonnegut and Kafka in middle school and loving how weird and darkly funny they could be. It's interesting, because I didn’t really have a moment where I felt that I “saw myself” in a book growing up, as some people speak about. I think that’s probably part of the reason why I wrote "True Biz", in the end.

More on books: Do you prefer reading printed books or e-books?

Print books! To each his own, of course, but I really struggle to read in an e-format. When I’m looking at a screen, it feels like my attention span shortens to expect the instant gratification we so often get from the internet or social media, and that makes reading less enjoyable.

You received high praise for your novel "True Biz" – one review calls the story an “unforgettable journey into the Deaf community and a universal celebration of human connection”. How so? How can literature break down language barriers?

There was some trepidation when I came to the table with "True Biz" about whether a very deaf story could appeal to a mass audience. But in a lot of ways, the book is a quintessential coming-of-age story (with a little coming-of-middle-age thrown in). Everyone wants to be understood, to find their place in the world, and that’s at the heart of the students’ struggles in the novel.

While I was writing the book, I grappled a lot with how I might be able to represent ASL—a three-dimensional language—on paper. Working with Brittney Castle, the deaf illustrator who drew the sign lessons for the book (s. image below), was such a fun and collaborative experience one doesn’t usually get while writing books. I also developed the system of visual dialogue tags, in which every character signs from a specific place on the page, as a way of representing some of the spatial grammar we employ in signed languages. I hope that in contrast to the very straight English dialogue sans quotation marks, readers can see for themselves that signed languages are not broken versions of spoken ones, but are their own entities.

© Brittney Castle

In one particular interview you said people often don't understand the social and emotional side of language – it can include, exclude, and help forge an identity. How so? Was it literature that helped you find the social and emotional side of language?

In that interview I believe I was talking about how important ASL was to my development as a writer, which is something people often find strange, given that I am writing in English. However, ASL is really foundational to the way that I process my thoughts and surroundings. So it’s probably the other way around—without ASL I wouldn’t have come to writing literature, because I wouldn’t have understood myself as a person worthy of telling a story, or the beauty and humor in the deaf experience that is embedded within our languages. That’s the social and emotional power of language—without it, it is hard to think or organize thoughts. And each time we learn a new language we open up other possibilities for understanding something new, too.

What is your take on the representation of Accessibility in literature? How can deaf voices and communities be heard, represented, and celebrated within literature and society?

Often I come across an attitude where people are genuinely trying to be more inclusive of marginalized voices, but they are also still thinking of it as a duty that can be checked off a to-do list. In reality, inclusion and diversity are living and ongoing processes. Deafness is a rich and complex culture, and readers deserve a multitude of books from different deaf perspectives. I started using the phrase and hashtag #DeafShelf, because it’s not enough for us to have one or two books about deaf people and tick that box; we need a whole bookshelf.

July also marks Disability Pride Month – highlighting disability culture, history, and community pride. Many people with disabilities within the LGTBQAI+ Community still face barriers to being fully included. How can literature change this?

One of the pleasures of literature is that it allows us to dip below the surface of our characters. Often in such a fast-paced world we are quick to relegate one another, and even ourselves, into a single box. But fiction allows us to wade into and revel in our complexities and our intersections.

It sounds a bit silly, but I’ve spoken with people before for whom it truly never crossed their mind that disabled people could also be queer. I think this comes from society’s tendency to infantilize disabled people, especially with respect to romance or sex. (In reality, statistics show that an above-average percent of disabled people identify as LGBTQAI+.) I know I’ve surprised some folks with characters in my novel having sex and using drugs, because it was not what they expected deaf people to do. To which I always respond, deaf people are people.

At its best, that’s the power of literature—to correct oversights, to cultivate empathy and connection between disparate worldviews. I believe ensuring that marginalized authors are platformed equitably and without tokenization, and especially working to publish and amplify the voices of multiply marginalized authors can change a lot. But the literary world needs to do more in both of those areas.

You are also a mother of two children. At Frankfurter Buchmesse, this year’s Frankfurt Kids Conference will be all about: "Children’s Books in a Fragile World". What are your thoughts and hopes in regard to children's literature in times of rising illiteracy but also in regard to young readers with disabilities?

There is so much work to be done in the field with respect to foundational literacy, as well as media literacy and hygiene today. As a parent it does overwhelm me sometimes. I’ve been working with my hard-of-hearing son using a specialized program that teaches reading via ASL, since he does not have full access to phonics. He’s been very successful with it so far, but most D/HH children don’t get that specialized instruction. As folks push to keep disabled learners in mainstream classrooms, the desire for “inclusion” can’t be conflated with one-size-fits-all education.

With respect to representation, I think children’s literature is making great strides in providing more books about disabled children’s experiences in the world. In a lot of ways children’s and young adult literature have been ahead of the curve on this. I hope that in the future, we’ll see more disabled characters in stories that have nothing to do with disability, just being well-rounded people, having mundane problems, and families, and enjoying life.

When you think about big events such as book fairs with readings, speaker panels, big halls filled with books and people - what things do you consider most important for visitors with disabilities to feel safe on one hand, and also included and welcome on the other?

As a deaf person, having skilled sign language interpreters is the quickest way for me to feel included at an event, though live captioning can be useful, too. Disability is a big category, though, so that answer will of course be different for everybody.

Often accessibility measures are tacked on retrospectively, after all the planning is finished and organizers realize they have left people out, usually because we disabled people have to chase them down and ask for access. I would love to see disabled people invited and included in the planning stages. Knowing that we have a say in what we need (and not having to beg for it) is, I think, the best way we can feel safe and included. This approach is also a great way to make sure we are supporting neurodivergent people, people new to the primary language of the event, folks who might be experiencing a new or temporary disability and don’t even know what accommodations are available to them, and more; universal design helps everybody.

Thank you so much again, Sara.

The interview was conducted by Lea Nordmann, PR trainee at Frankfurter Buchmesse.

More about Sara Novic: https://sara-novic.com/ (opens in a new window)

More about Disablity Pride Month: https://thearc.org/blog/why-and-how-to-celebrate-disability-pride-month/ (opens in a new window)

Frankfurter Buchmesse offers translations into sign-language for multiple events during the fair. More about accessibility at Frankfurter Buchmesse: https://www.buchmesse.de/en/visit/accessibility